That phrase, “a scene developed,” is a modern usage of the word “scene” that hasn’t been handled well by the dictionaries, even the online ones, as far as I can tell. The American Heritage Dictionary (4th ed.) comes as close as most, which is pretty bad: “A sphere of activity: observers of the political scene.” A OneLook search brought this: “a particular interest or activity, and the people and places that are involved in it” (MacMillan), which is slightly better, as is wiktionary’s “A social environment consisting of a large informal, vague group of people with a uniting interest; their sphere of activity.”

But none of these definitions is adequate for the Ingram quote above. They are too passive, as if “activity” just happens and the “scene” is the “sphere” that denotes the activity’s boundaries. Nothing is said of cause and effect, nothing is said about value.

This new usage of “scene” needs a more extended definition, so here’s mine:

Short form:

What is a “critical number”? However many it takes to make a scene. It probably depends on how creative each is, and maybe their manner of interacting.

“Creative,” by the way, can apply to any exercise of skill, usually intellectual, but not always artistic. There are philosophical scenes. There are scenes where theoretical physicists inspire each other’s work. Programmers at Google seem to have a kind of scene going that’s igniting some exciting web activity. I want to exclude, however, phrases like “political scene” and “drug scene” from this definition. Those really do seem to be mere “spheres of activity.” Let’s reserve our definition of “scene” for the spark struck between creative minds.

The size of the geographic community in which the creative people live does not seem important for a “scene” to develop. Concord, Massachusetts, by anyone’s standards, had a hot literary scene in the middle 1800s. Concord even today is only about 17,000 people (wikipedia) and in Emerson’s day it was barely over 2,000 (Traditions and Reminiscences of Concord, Massachusetts, 1779-1878 by Edward Jarvis). And yet:

In fact a large urban setting may be an obstacle. This same wikipedia article cites a review of an interesting-sounding history of the Concord literary scene called American Bloomsbury by Susan Cheever. The comparison to Bloomsbury is significant: another community-based literary “scene,” though quite a different setting. Virginia Woolf and other intellectuals isolated in a toney London neighborhood achieved a scene of their own.

In the modern global culture, the size of the geographical community is probably irrelevant; in some cases there may be no geographic center. But a small group of people meeting regularly over their artistic endeavors can create a scene nevertheless. They don’t need the globe, though they benefit from outside influences. They don’t even need a metropolis. In fact they don’t need Concord. All they need is communication with each other, seriousness about the importance of their work, and the time to do it.

Apparently socioeconomic class isn’t a barrier either. Consider the music scene that developed in the Mississippi Delta country among some of the most poverty-ridden, oppressed people in America. It gave us bottleneck blues and Robert Johnson, among other things. But they had a scene going. That scene is portrayed well in the book and movie The Color Purple by Alice Walker, in the juke-joint passages.

The idea that “scenes” just “develop” is only partly true. Scenes are surprising bursts of activity that give us new genres, artists, and creations, usually startling even the artists themselves. Still, a scene develops only where artists are working together. It’s happening right now, in your head and mine.

© 2010 Greg Bryant under the Creative Commons

Really interesting article, Greg. It’s certainly something I hadn’t thought to think about.

I wonder if you would include fandom in your definition of scene. The “Star Trek” fandom built rapidly after the announcement that NBC would cancel the show at the end of the second season. A lot of creative work and stamps went into badgering the network into reversing course. Since then, fandom kept the franchise alive into and through several films and spin-off series, hundreds of books, I don’t know how many fanzines, and conventions. Geography has been important in some cases, with local clubs, but the larger scene is worldwide.

The World Wide Web permits scenes to be made rapidly. People have no more in common than an interest and an Internet connection. That connection is what makes the scene for the creatives to mingle their minds. Blogs, forums, chat rooms, social media … these are the loci of the scene.

That’s a good point about fandom. I don’t know what to do with the fans. Obviously they’re often important: creative people generally create for an audience, whether for fame or money. The fans supply those. In some scenes, fans are essential: blogs, music, literature… in the back of the artists’ minds, at least, is the end goal of public performance.

But they’re not always necessary, either. Philosophers and theologians bounce ideas off each other with almost no one but themselves as audience. They publish, but it’s either that or perish. Philosophers publish to make money to think. Songwriters think to publish to make money. Bloggers think to publish to have an audience. What all these scenes have in common is artists.

If fans are necessary, or desirable, they may or may not be creative elements. The artists and their relationship are the heart of a scene in any case, as I understand the word “scene.” If there is no creative elite, it’s a different kind of scene: drug scene, for example. “A sphere of activity.”

It’s another question whether trekkies’ support stimulated “an efflorescence of new ideas” or “superior work” after the initial series ended, but they certainly stimulated productivity. This led, no doubt, to competition between writers and other challenges to creativity.

I take your point about the fans generally standing outside the scene itself — the nuclear scene, perhaps. I think there can be a fan scene (whether with “Star Trek” or “Buffy, the Vampire Slayer” or The Grateful Dead) in which the creative energies of the fans feed the original artists to such great degree that there would be no new art without them. But they are not, as you point out, the original scene and it would be well not to confuse them.

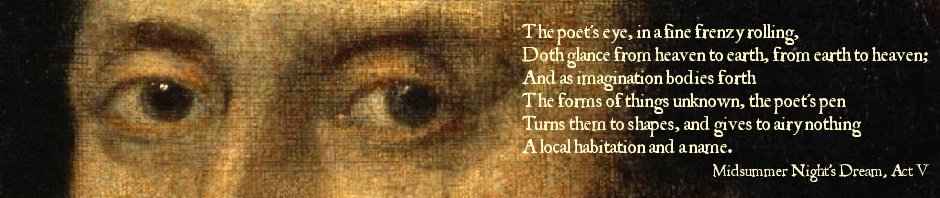

I do believe I have undervalued the fans. The more I think about it, for many scenes they are actually a creative element, or contribute their “creative energies” as you say. Shakespeare was part of a theatrical scene in London that could not have existed without a regular theatregoing audience that could “get it.” They could hear a verse play and understand what they heard on a poetic level, which is a sophisticated audience indeed. They weren’t only gentry, either. They were trained in theatre appreciation simply by going to the theatre. (I’m spelling it that way because WordPress or the browser or something prefers British spellings and underlines American spellings in red.) Shakespeare wrote, as far as I know, nothing esoteric. His plays were designed to appeal to the crowd, from the Queen to the groundlings. He was a professional and the fans made the scene for him. He was immensely successful because his fans demanded excellence and he learned to provide it. So I agree that the definition of “scene” has to be kept loose enough to allow for varying degrees of fan creative collaboration.

I was going to suggest using my definition above as definition 1, and then following it with a second definition. Then I re-read my definition, and “creative persons” is generic enough to include a sophisticated fan base.

So I thought: “Enlarge the extended definition, just above it, to clarify the inclusion of fans.” But then I noticed the last sentence of it:

I think a fan base was the kind of thing I had in mind with the word “social.” For performance artists it goes without saying that the quality, involvement, and responsiveness of the audience are important. But for the general public, is there another way we could phrase the def to accommodate the creative input of fans more explicitly?

A cogent take on the term “scene” and you demonstrate clearly that laggards and slugs had been assigned this word in various references in days gone by.

I take some issue to the concept that large metropolitan areas can be a drag on a burgeoning scene. If you read a biography on Emerson, you see that he was influenced by many individuals who had passed through Boston or resided there. Many of the artists involved in the Concord scene had gone to Harvard-which was across the river from Boston-but heavily influenced by the city. The Mississippis Delta Blues became deeper and richer when others discovered it and tooks the ideas back to Chicago, Memphis, St. Louis, etc. and my guess is that those places bounced ideas back down to the delta when those city musicians traveled down to the Delta to visit family members or perform.

Good points, and I know Robert Johnson, “King of the Delta Blues Singers,” was well-traveled and not just an ignorant country boy.

Another thing about fans that deserves mention: the other day I realized that a critic can be defined as “a fan who is unusually articulate about expressing appreciation.” Critics describe, analyze, infer, synthesize, and evaluate.

They are a two-way street. On the receptive end, critics’ skillful articulation of what others already feel increases public understanding and appreciation. On the expressive end, critics are the fans’ voice, just as any successful journalist is really asking questions the public would ask if they had the access and the ability to phrase their questions well.

Most of us would agree that intelligent criticism is important to creativity, since we’re trying to do that for each other in this medium. If we recognize critics as representatives of fandom, we automatically include the fans in the creative process.